Customers

The Sunwise Turn usually received favorable press. Stephen Graham, however, noted when reviewing Jenison’s memoir that she talked too much: “I was talked to so much on my first visit I hardly dared put my nose in the shop again–charming talk, but too much.” This may have been part of Jenison’s strategy to gain information about customers in order to better sell books to them.

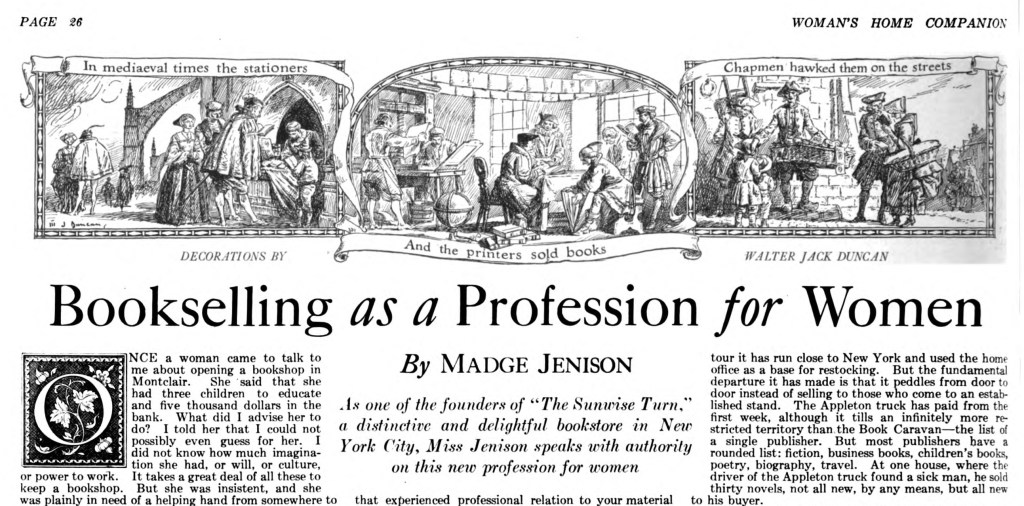

In a 1922 article for the Women’s Home Companion, Jenison wrote that “A GOOD card catalogue of customers is one of the richest assets a bookseller can have, and she should begin from the first to create it.” She notes that personal information contained in such card catalogues are becoming important in many professions and businesses. Today businesses gather information about customers from their online behavior and purchases, but as Jenison writes, in the early twentieth century “You get this information day by day from people who lean on their elbows on the tables opposite you and lay before you their tastes, hates, needs, and sometimes stories out of their lives more poignant and brilliant than anything you have in print” (Bookselling as a Profession for Women). Booksellers and other retailers use this personal approach today with regulars.

A cover story in the New York Tribune on December 16, 1917 praised the bookshop as having “the atmosphere of the bookshop before it was commercialized; when bookselling was a profession and not a business.” The writer of the article, Elene Forster, goes on to describe their personal touch, “Every book which is sent out of the shop has pasted on the inside cover a little critique written by Miss Jenison or Mrs. Clarke. This means, of course, that every book which leaves the shop has been read by one or the other of these faithful souls.”

Another writer noted that Jenison and Mowbray-Clarke “really know the meaning of the personal bookshop, not entirely obscured by commercial considerations.” They wanted to “promote more original creative work among those in the arts and crafts by supplying them with the proper tools–books that inspire them to originality rather than encourage them to imitate others” (The Daily British Whig, Nov 5, 1919, page 12).

This was much like Sylvia Beach’s work at Shakespeare and Company which opened in 1919 and a few years later famously publish James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922. The Sunwise Turn also had a publishing program. In a letter to Sylvia Beach, Mowbray-Clarke wrote that Sunwise had wanted to publish Ulysses in the United States, but it was not a project they could support financially at the time. The Sunwise Turn published books and broadsides and famously held readings with poets and authors.

Contemporaries

Jenison and Mowbray-Clarke had dozens of women interns work for them to learn the trade and help out in the shop. Famous among them was Peggy Guggenheim. Both booksellers also spoke with women from around the country, both formally and informally, who were interested in opening a bookshop.

In a 1915 article published in the influential literary magazine, The Atlantic, Earl Barnes proposed that the surplus of college educated women consider opening their own bookshops as more stores were needed throughout the country. The Sunwise Turn opened before this article came out. Jenison and Mowbray-Clarke were initially inspired to open their shop to help spread what they considered good books and modern ideas, literature, and art. The success of the Sunwise Turn and other women booksellers or bookwomen who worked in high-profile positions like Blanche Knopf or Marcella Burns of Marshall Field’s in Chicago, no doubt inspired other women.

Jenison’s work as a member and president of the Women’s National Book Association put her in the position to directly advise other women booksellers and those interested in opening shops. Her 1923 bookselling memoir make have been inspired by the obvious interest in the subject.

Later 20th century

In 1975 the American Booksellers Association celebrated their 75th anniversary. It is striking that multiple quotes from Jenison are included in their commemorative monograph, Bookselling in America and The World, ed. by Charles B. Anderson. In fact, Jenison’s quotes open and close the book. At the end of his forward, Charles Burroughs Anderson uses this quote from her memoir, “If people get to believe that you know about books, you will sell books all right” (p. x).

The last essay of the book is a reprint of a 1908 essay written by Mark Twain. [This has nothing to do with the essay or the quote, but an interesting tidbit is that Twain and Jenison were neighbors in New York at one point.] The editor chose three quotes from Jenison’s memoir to close out the book. No page numbers are provided and there is no sense that these quotes are from different parts of her memoir. Quotation marks are used. They are:

“There is nothing in the world except a battle like the two weeks before Christmas in a bookshop. There are whole days in which one does not eat anything or have a glass of water or wash one’s face. It is like being the mother of ten thousand children and having them all come in at once for cookies and to have their mittens dried” (p. 197)

It is obvious why this quote was included. It is amusingly hyperbolic, but it captures the feeling of what it is like to work in a bookstore during the holiday season. The second quote is,

“If you go into any automobile salesroom on Broadway and indicate that you are going to buy a car, the salesman will talk to you for two hours. He can tell you about his car from the bottom screw to the top. But if you ask in a bookshop for Irving’s Sketchbook, the little girl says sweetly, “Who wrote it, please?” and then she asks somebody else and they ask somebody else, and at last they bring the head of the department from the balcony to ask you if you know who the publisher is” (pgs. 197-198).

This quote is on the more serious side and has to do with booksellers actually reading the books that they sell, which is something Jenison and Mowbray-Clarke initially strove to do and which may have been a goal in constant striving rather than reality (I speculate that they might carry books recommended by trusted friends or colleagues.) Jenison’s point is that booksellers should know their books in order to make appropriate recommendations rather than just order in quantities of books that publisher’s are pitching. She gives a poignant example of the importance of making appropriate recommendations: she writes “when you are a shuddering young soul who has just heard that her husband is dead in the Somme mud, [the typle of bookseller she is arguing for] will find you some books that will tell you a way to go on” (p. 29).

And the last quote is,

“Our theory was that people are baffled by libraries–when you are confronted by 20,000 books, you will read nothing, but if you have at hand 15 which you feel to be the best current material on any subject important to you, you will read them all. The whole pattern of democracy seems to have become too large. “Our theory was that people are baffled by libraries–when you are confronted by 20,000 books, you will read nothing, but if you have at hand 15 which you feel to be the best current material on any subject important to you, you will read them all. The whole pattern of democracy seems to have become too large” (p. 198).

This quote is in regard to book lists that Jenison and Mowbray-Clarke made focused on subjects or aimed at particular types of readers. Creating these lists was time intensive labor. They even attempted to advertise in this fashion until they realized not everyone who saw these lists would purchase the books through the Sunwise Turn.

The 21st century

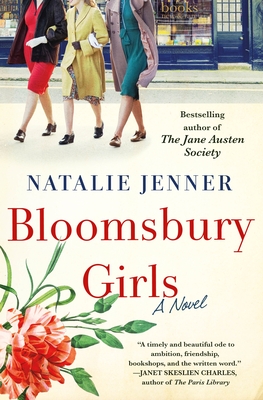

The Sunwise Turn recently made an appearance in a new novel, Bloomsbury Girls by Natalie Jenner published in 2022. The plot revolves around three women who work in a London bookstore in 1950 and buy it, renaming it Sunwise Turn in honor of the original. And writer Joanne O’Sullivan announced in an article about the bookstore on Lit Hub that she is writing a novel “about the women of the Sunwise Turn.”

It’s exciting to see book history being written and recovery work in action — from historians who are studying bookstores to women scholars writing women back into history to book women honoring foremothers in fiction. The Sunwise Turn may have closed in 1927, but it has continued to spark the curiosity of all who come across. it.